January 18

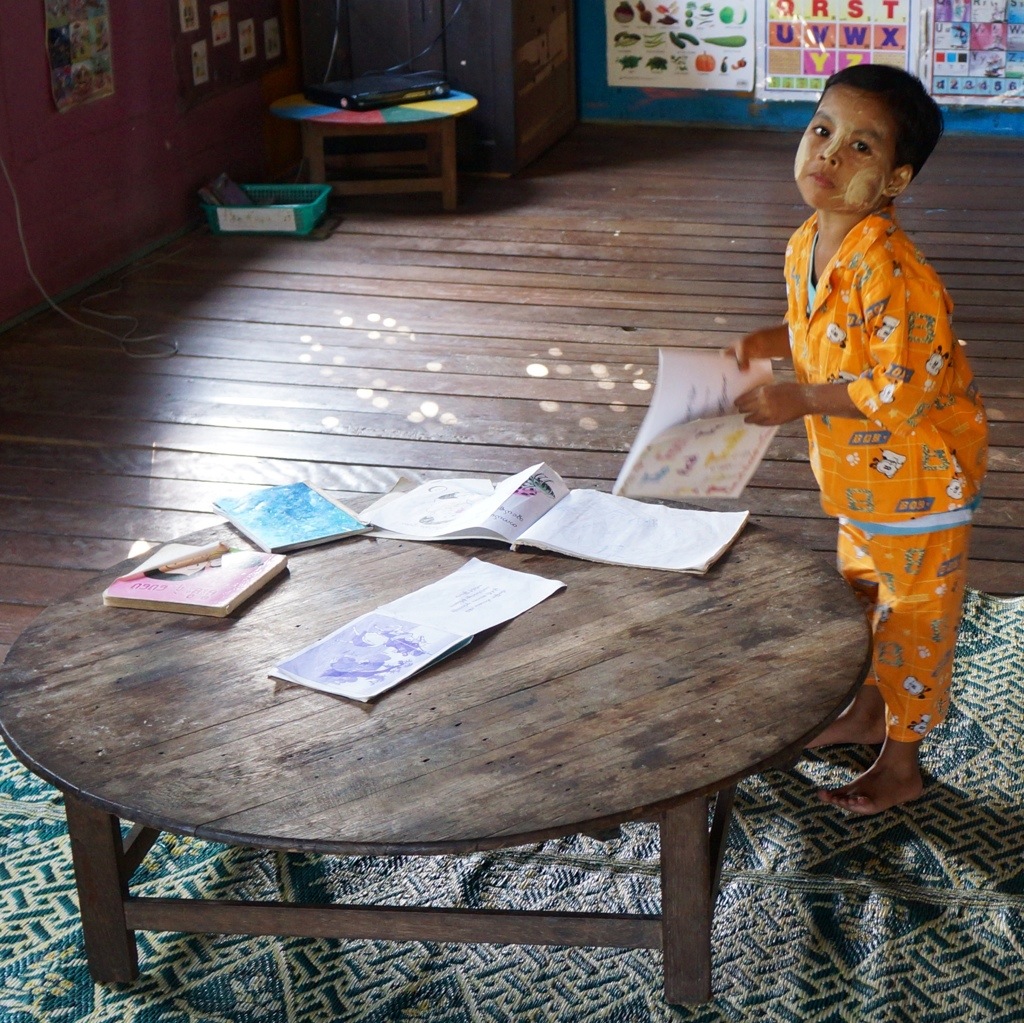

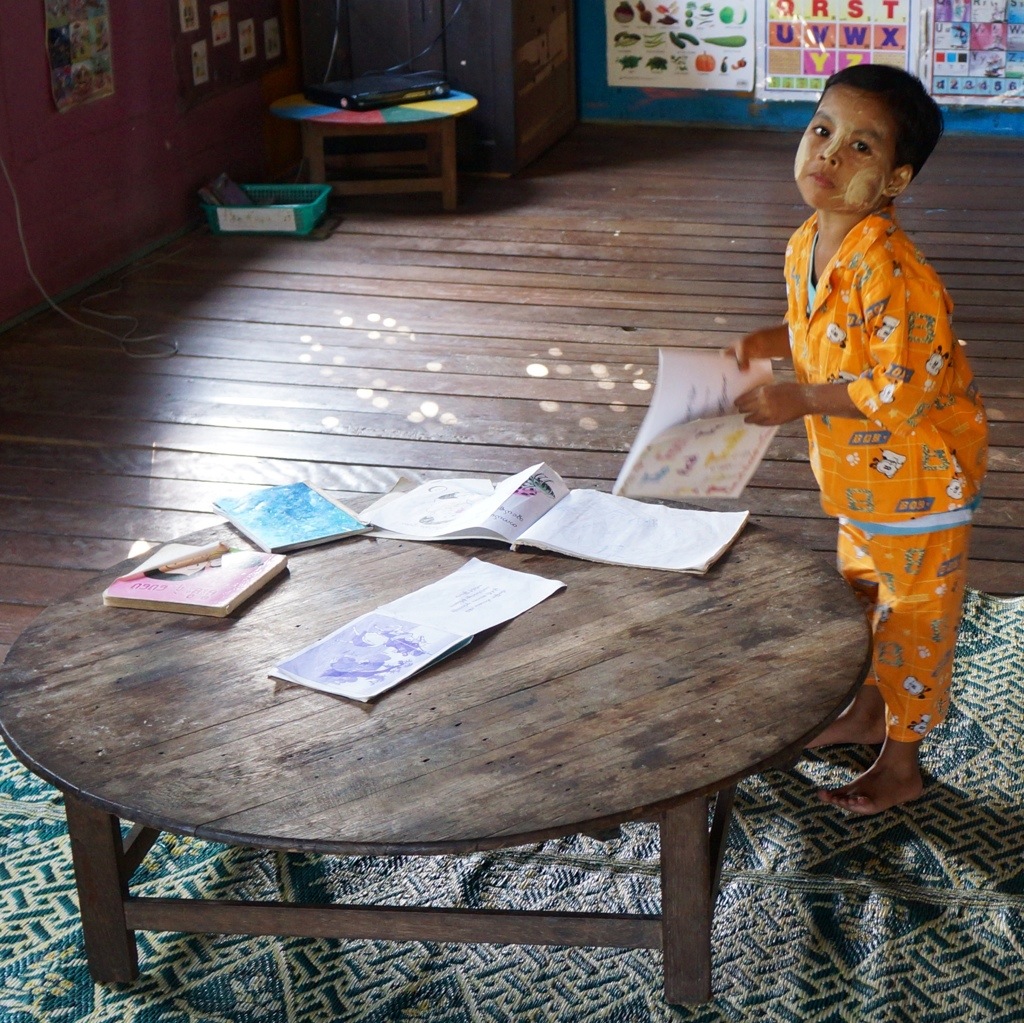

Another great buffet breakfast at the hotel, then off to Blossom Nursery School. Thirty or so tots are engaged lovingly and enthusiastically by two young teachers. Many of the children come from disadvantaged families. Hillary, there to observe with us, jumps in fully participating with the young children in a delightful way.

We drive to the offices of Hope International, an NGO engaged in reconciling conflicting groups in trouble areas of Myanmar by humanizing all elements. We are hosted by Maung Hla Thaung, a large man with a loud voice and an animated face with an infectious smile. He is originally (and still) a talented carpenter/wood worker. In a self-effacing way, he talks about work he does in a few small, rural villages in the north of the country. He brings a small number of people in to Yangon for training here on leadership and related matters. He is quite upbeat, suggesting that relations between people there are not as bad as the press portrays them and holding out hope that common ground may be found. Interestingly, he sees little difference in the situation under the new leadership in the country.

We ride with Maung Hla Thaung to a house that he designed for a wealthy friend. He is not a certified architect, but has very strong views on environmentally sound architecture. He is far more concerned with the interior of the house, the floor plan, than the exterior and insists on interviewing all family members about their prospective uses of the house. He will build only utilizing recycled materials. He has designed all of the furniture in the house he takes us to see, as well as the house itself. A portion of the house involving a swimming pool and deck spaces, is quasi-public, open to use by friends of the owner at will and without notification to him. The entire house, including all of the furniture, done of recycled teak and different types of brick is quite spectacular, though the owners will win no neatness awards from House Beautiful. We are convinced to stay for a light lunch, which turns out to be rather elaborate, prepared by servants. We leave without seeing any family members.

We drop off Maung Hla Thaung and drive to Mesmeah Yeshua Synagogue, which under the British in the 19th century had some 2500 members, now down to about 20. We are shown around by Sammy Samuels, a Burmese who lives in New York and runs Shalom Tours to Myanmar. He is an engaging and welcoming young man, who shows us around the Sephardic synagogue, with its two silver-clad torahs. Recent group visits, one including the President of Brandeis last week, have Sammy very energized and he tells us about an event planned at Yangon University on Holocaust Memorial Day on Jan 28, which Carol and I may try to attend. Dotty has joined us at the synagogue and is quite interested in having her students attend. The visit to the synagogue proves far more interesting than I’d anticipated. We say our goodbyes to Dotty, make a contribution to the synagogue and head back to our hotel, where we lounge by the pool, have a drink and try to prepare for a very early departure to Mandalay tomorrow.

Our driver picks us up and drives us to The Strand Hotel, for drinks with Joe and Cathy Feldman, Chicago friends who have been touring Myanmar. Moe’s cousins, Peggy and Gary from Las Vegas, were also in town and came up to the Feldmans’ room for some wine. We then went down to the informal restaurant in The Strand for dinner and to exchange travel stories. The Strand is a good old world hotel, but we are very happy to be staying at the Governor’s Residence to which we returned before 10 PM.

January 17

Great buffet breakfast eaten outside overlooking the garden at the hotel.

Picked up by Hillary and driver and taken to the Lumbini Academy, a bilingual school for pre-kindergarten through 12-year olds, where students are taught not only English, but to read and write Burmese, which they otherwise would be able only to speak. We are shown around the classes by the administrator of the school and see everything from a pre-K duck, duck goose game

We go on to the house/ gallery of U Hla Win, who spends more than an hour showing us around and talking about his amazing collection of everything, including ancient ceramics, old valuable paintings, artifacts from monasteries, old solid wheels from oxcarts, and the work of modern painters he supports, which bulges from every wall and corner of the attractive old home. U Hla Win used to have a large gallery, but had to close it under the military rule. With the help of an American Buddhist/architect, Damon, he plans to expand his gallery at home and to reopen it to the public rather soon. We are hoping to meet Damon on our return trip to Yangon. U Hla Win used to be a pilot, but developed this passion for art. He is also a novelist and journalist who has been awarded recognition by the government. He’s a good example of Dotty’s efforts to put us in touch with people, even though she has never met him (she knows of him through Damon).

From here we drive a very short distance to Kyaik Kasan, a small pagoda Hilary’s mother goes to. It is fun to walk around this small, active pagoda in contrast to the fabulous, large Shwegadon Pagoda that we saw yesterday. Some 80% of the people in Myanmar (which, by the way, is pronounced, me-ah-ma) are Buddhist.

On the streets we pass, we see many people carrying umbrellas as protection from the sun. People also color their faces with a yellowish powder/paste, called, thanaka, made from wood, which serves both as protection from the sun and as a cosmetic. Stray dogs are both visible and audible. There is no visible sign of the military at all. Hillary has a quick lunch at a nearby Thai restaurant, but Carol and I, who are still full from our large breakfast, have only a drink.

We drive on from lunch to a day care center. What a surprise for Carol and me, who were expecting to see a place for the care of very young children. Instead, we are ushered into a building that houses the Support Group for Elderly Doctors and introduced to it’s 89-year old president, Dr. Myint Myint Khin, a retired gastroenterologist, who in turn introduces us to the group of elderly women doctors and professors, who have just finished their monthly lunch discussion. The organization is the brainchild of Dr. Myint Myint Khin, who says that older people may not always need financial support, but they certainly need the social and moral support that comes from being valued, especially by youth.

Her organization provides moral and physical support for its members, looks after their needs and also produces booklets on a wide range of topics. Dr. Myint Myint Khin is a force, with strong opinions on a wide range of issues that we were treated to in about an hour of private discussion. Surprisingly, we learned that women had long been valued in Burmese society and made up a very significant proportion of prominent members of every group except the military and politics. She attributed this to Buddhist views of equality. She was an outspoken critic of the military who had “incarcerated” the country for fifty years, and had no fear of speaking out, since there was nothing she felt they could do to her that would harm her or her reputation. She is hardly resting on her laurels and aims to extend the benefits for doctors to all elderly people, perhaps using public squares a day a week for the purpose. It would be foolish to bet against Dr. Myint Myint Khin. On anything.

We drove downtown and walked around Independence square, looking at some of the old colonial buildings and seeing the palm readers along the street. Driving on, we passed the Sule Pagoda and saw another Yangon lake. In another area, we parked and Hillary led us on a labyrinthine route, across a bridge through a market area and up some back stairs to a wonderful handmade textile shop called Yoya May, run by Peter, the mother of another Pre-Collegiate Program student, who will begin Carleton College in the Dallas. When we admired a design on a blanket and asked whether she had anything like it in a runner, she promised to have one woven and sent to us via Peter.

Walked back to the car and were driven to Yangon Diplomatic School, which houses Dotty and Jim’s Pre-Collegiate Program (PCP), which they started about ten years ago with a Burmese friend from Yale, who has since died. About 12-15 students are selected for the 17-month program each year from among 30-80 applicants. Students receive training in English and critical thinking. The program has a half-day-a-week service component and after a year, students are place in work internships, often in NGOs. Graduates are placed in universities in the US and Japan. At the school, I talked to a very impressive student, Aung Hein, who graduated from Earlham College, was awarded a Corro Fellowship and is now back teaching at PCP. He plans to teach a course on happiness next year, so I am giving him our copy of Travels with Epidurus and told him about Stumbling on Happiness, a great book by a Harvard psychology professor. We attended a dress rehearsal of three 1-act plays, written and performed by PCP students, which was extremely amateurish.

Drove in heavy traffic to Hillary’s apartment building, which houses some thirty apartments. Hillary has written a very nice paper about what a caring community residents of the building are. Technically, they rent the apartments, paying the government 63 cents a month, but the apartments are salable. Hillary’s mom prepared dinner for us in the small apartment that once housed eleven family members, and now is home to Hillary’s parents, her and her 27-year old brother P.L., who handles travel and other logistics on behalf of NGOs. Her father used to be a seaman, away for three months at a time, and is currently looking for work. Hillary’s grandparents lost a successful restaurant to the military government, and they and all six of her Mother’s brothers died in about a five year period that ended when Hillary was thirteen. Her parents gave us a calendar with monthly photos of Aung San Suu Kyi and we gave them a CD with American music. After a pleasant dinner, we were driven back to the hotel, once again rather exhausted.

January 16

Our flight to Yangon is delayed an hour, and we have some difficulty finding Dorothy and Hillary, but if this is our major travel snafu on the trip, we are in very good shape. (I have, and probably will continue to refer to Dorothy as “Dotty,” which is the name friends call her in the US. because of the English influence in Myanmar, though, “dotty” has the connotation of “crazy,” so Dotty goes by Dorothy over here.). A driver and representative of the travel company and Hillary accompany us to our home in Yangon, the Governor’s Residence. This is an absolutely delightful place with gardens, swimming pool, a lot of beautiful wood and artwork around the place, which we pass en route to our very spacious, comfortable and nicely appointed garden view room. Because of the increased popularity of the country, it took our travel agent, Thiri, some time and effort to land us a place in the Governor’s Residence, but we are very happy that she was successful, as it will be a most comfortable home for us in our two stays here.

Instead of having lunch at the hotel, Hillary suggested we go to a local Burmese restaurant, called Feel. This is a very bustling place where food is laid out, people look at choices and waiters bring the food to the table. I was not hungry, but Carol enjoyed lunch.

After lunch, we were driven to Proximity Design, a place where Hillary works. This is a very interesting operation, founded by an American MBA, Jim Taylor, and his Burmese American wife, Debbie. We spend a couple hours there and have a chance to talk with Jim briefly. He says that farmers have been hurting because of government policies that keep the currency value artificially high, thus hurting the price of rice, but helping the gem industry in which the military and its supporters have large interests. Because of the trips that Carol and I have made to rural villages in Ghana, we are particularly interested to learn about this operation.

Here is Hillary at Proximity:

Here is a short description of the work that proximity does.

Proximity Designs is a non-profit social venture working to reduce poverty and hunger for tens of thousands of rural families in Myanmar since 2004.

We address extreme poverty by treating the poor as customers and offering innovative and affordably designed technologies and services. Our customers are families who earn their living by farming small plots of land. There are an estimated 10 million rural households in Myanmar. Our offerings include foot-operated irrigation pumps, drip irrigation sets, water storage tanks, solar lanterns, financial services and farm advisory services.

Our eighteen different products and services are designed to dramatically reduce daily drudgery, hardship and improve household productivity and incomes by replacing time-consuming and antiquated technologies. For example, our customers replace their rope and buckets for our foot-powered irrigation pumps and typically double net seasonal cash incomes ($200-300), money they can then use to buy food, send their children to school, reinvest in their farms and more.

To date, Proximity has delivered more than 180,000 products and services to over 77,000 rural households in Myanmar.

Our model: discover. design. deliver

Drawing on human-factor research methods used by the world’s leading innovation firms, we spend countless hours observing and interviewing rural households, learning what they value, identifying root problems and most important, developing empathy that leads to lasting solutions to the problems they face.

The insights we glean from intimate exposure to customers are what drive Proximity’s on-site product design lab. Located in Yangon, our lab designs and creates products exclusively for people living in poverty in the Myanmar context.

Products are manufactured locally and reach customers through a nationwide distribution network linking independent agro-dealers, village entrepreneurs (product reps) and village-based groups. Our delivery infrastructure spans an area where 80 percent of Myanmar’s rural population lives.

Linking up to national economic growth

Proximity understands that sustainable well-being for our customers depends on a supportive macro policy environment. To that end, we’ve leveraged our extensive, on-the-ground knowledge of rural conditions, teaming up with Harvard’s Ash Center to research and analyze Myanmar’s rural economy. We’ve produced several groundbreaking reports that have helped inform key policy makers in Myanmar.

How we measure our impact

We have a dedicated team within Proximity that comprehensively assesses the impact of our products and services. For the past several years we have conducted an annual impact assessment from a random sample of approximately 450 rural households, measuring the income increases families have achieved as a result of using one of our products. For example, we have documented that a household can increase their net seasonal cash income two-fold, by roughly USD $300, as a result of increased productivity from using the foot pump. We have also found that this additional income was used for purchasing more food and better diets for the household, paying children’s school fees and for farm inputs for their next crop. We have also conducted economic studies in multiple rural communities to estimate the multiplier effect of increased farmer net incomes on the larger economy.

After a couple hours at Proximity, we drive to the apartment home for a doctor. Unfortunately, her daughter tells us that she has been called away to an urgent meeting and so we rescheduled for tomorrow.

We are picked up by the father, Aung Moe, and brother, Pyae Phyo Hein, of the Northwestern student from the Myanmar, Arkar Hein (by the way, I learned that the Burmese have no surnames, so, though we’ve called him “Arkar” we should have been calling him “Arkar Hein”), who Carol and I have gotten to know in Evanston. His father owns a shrimp processing operation on the Bay of Bengal, near Bangladesh, an area that has experienced ethnic difficulties. He sells mainly to Japan, since sales to the West were cut off by trade prohibitions for many years. China, he says, wants volume, not quality, but Japan is willing to pay for quality. Aung Moe confirms Jim’s views that government currency policies impede sales.

We have tea with Arkar’s parents and family. His mother, Mu Mu Shein, is lovely and gracious, but speaks no English. Pyae Phyo Hein is finishing his sixth year in medical school (a resident), and thinks he may go into pediatrics. His lively, well-traveled grandfather, who is 84, and his very quiet grandmother, who along with Aung Moe’s two younger brothers and their families, live with them, join us. His grandfather speaks Mandarin, used to trade beans, and speaks a little English. They give us some lovely gifts because they are grateful for our looking out for Arkar. We have brought a CD of American music, which we give to them. Aung Moe has three older sisters, one of whom lives in San Francisco and who we met, because she traveled with Arkar when he first came to Northwestern. Here’s a lousy picture of the group (sorry).

From there, we go with Hillary and Pyae Phyo Hein for sunset at Shwedagon Pagoda, the most famous site in Yangon. The pagoda dates back 1000 years, though it has been added to and altered many times. It is a very actively-used site, with many people there to worship. There are many different shrines, which we see as we circle the shrine, clockwise. It is very difficult to convey the scope of the site but some photos may at least give you some notion of this impressive, living monument.

From the pagoda, we are driven a short distance for dinner at a very nice restaurant at which Aung Moe has reserved a private room with a view of Shwedagon for us. We are joined by Dotty and her husband, Jim, along with Aung Moe’s family, minus grandparents. We are also joined by Khine Zin Thant, a graduate of Dotty’s school who is a sophomore at Vassar.

Jim is a very engaging fellow who Dotty met at Yale and who has lived here with her. He has taught at three or four universities in the area of public management, consulted with the State Department, the New York Port Authority and others. Jim as wide-ranging interests, including singing with a Russian chorus at Yale and running. He clearly has a lively intellect and a good sense of humor.

Over dinner, we talk about the changes taking place in Myanmar, the name Myanmar versus Burma and the stopping of a huge Chinese dam project, through public pressure, stoked by the newly freer press. Mutual concern about China is a strong impetus to burgeoning relations between the U S and China. Aung Moe participates actively in the discussion.

By the time we return to our hotel, we are more than ready for a shower and sleep, but I take a bit of time to download the day’s 100 photos.

January 14-16

It’s in packing that you start to wonder. First, there’s the malaria medicine. Next the pills for nausea that the malaria medicine may cause. Then, there’s the sun block, because the malaria medicine makes you prone to sunburn. Throw in a vial of pills for diarrhea, just in case you pick up some bug. The insect repellant to, well, repel insects. And, this trip, a heating pad, because my damn lower back has been hurting.

You cram in more clothes than you’re going to need, despite your vow not to do that, not this time. Time to head out to the airport, arriving two and a half hours before your flight to Hong Kong, a mere 15 1/2 hours, before your layover of about two hours there and then continuing on for your three hour flight to Bangkok, where you plan to grab some rest before your 9 AM flight to Yangon, a brief hour and twenty minutes. Altogether, you leave on Monday afternoon and arrive on Wednesday morning, having crossed the international date line, and flown some 9200 miles.

So, is it all really worth it? Oh, yes.

En route to Hong Kong, I read two books, Michael Chabon’s latest, Telegraph Avenue, which I do not love, for our book group and a quite delightful book called Travels with Epicurus, given to us by our friend, Mike Lewis, which consists of philosophical musings on old age. Having both turned 70 recently, this is something on which Carol and I might well muse. I’ve been searching for the right term to describe where I’m at. “Adult” is too general and vague (and, in my case, probably not accurate), “middle age” is clearly a lie (how many 140-year olds do you know?) and “old” seems somehow too stark. I think I’ve finally got it, though. I am in my business class years.

Business class makes all of this travel a good deal more tolerable: special, short lines checking in and through security, club lounges with food and drink, early boarding, comfortable, reclining seats and better food. Maybe even a chance to sleep (I’ll get back to you on that one). For the most part, we’ve been able to do that on frequent flier miles, but I’ve about decided that, even without that, I’m now in my business class years. You might not have realized that I was such a philosopher.

Everything went smoothly, as scheduled (sleep on the plane, not so much). Arrived at the airport hotel, a Novotel in Bangkok, which boasts that it was rated the fifth best airport hotel in the world. All we want is a bed.

Truth is, Carol and I are very excited about this trip. We’ll be in a very different, interesting land that is undergoing a huge transition and, because of our friend Dotty (if you didn’t read the first post, please do to get the background), we will be experiencing it in a way that other visitors cannot. It’s been two years in coming, with one cancellation along the way, but we’re ready to go.

A day or two ago, we received an email from Hilary Myint, a graduate of Dotty’s school, who Dotty has enlisted to show us around Yangon. Hilary (also known as Yu Zind Htoon) wanted to know what we’d like to do in Yangon, and my reply to her, which I’ve copied below, is a pretty good summary of what we’re hoping for, and may be a good way to set the stage for our arrival in Myanmar:

Let me try to describe what interests us most, so that you can think about what would make sense for our stay in Yangon (actually two stays).

Carol and I are passionate travelers. What interests us most, wherever we go, is the people and the culture (religion, politics, the arts, etc). We are privileged to be traveling to Myanmar at a most interesting time of transition. We are would love to see how that transition is affecting people’s lives. I am sure that in ten years, Myanmar will be a dramatically different place. We are interested in seeing things now that visitors in ten years may not be fortunate enough to see or experience. While we are tourists, and so are interested in seeing things that we really should see as tourists, we have consciously decided not to do a typical tour of Myanmar and, because of Dorothy, have the opportunity to see the country in a unique way. So, we are interested in the central areas of Yangon, but we would also love to walk through neighborhoods where people live.

I am an avid photographer and will want to take many photos, particularly of people doing what they do. What seems to you ordinary day-to-day stuff may be very new and different to us. You can be a great help to me by explaining to people who may be a bit shy about being photographed that I am genuinely interested in them and what they do and am not photographing them because I regard them as “curiosities.” Carol’s background is as a psychologist and a poet, so if there are things that fit those interests, that would be great.

Finally, I hope that this will be a two-way street. You will be coming to the US for school soon and probably have many questions about that. To the extent you think it would be helpful, we are happy to talk about any aspect of what you may find when you get here.

Carol and I look forward to meeting and being with you, and appreciate greatly your taking the time to show us around.

And, in the next post, the adventure begins.

Well, we’re leaving in a week, so isn’t it about time that you started getting ready?

Carol and I planned this trip for October, 2011, but, when our son-in-law got sick, we cancelled. The Myanmar we’ll be seeing is a different country than we’d have seen only a bit over a year ago. Though I don’t necessarily attribute all of the changes in the country to our planning a trip there, here are the remarkable highlights of what has happened in less than two years.

2011 March – Thein Sein is sworn in as president of a new, nominally civilian government.

2011 August – President Thein Sein meets Aung San Suu Kyi (Nobel Peace Laureate, who had been confined to house arrest) in Nay Pyi Taw (capital, but little-visited city).

2011 September – President Thein Sein suspends construction of controversial Chinese-funded Myitsone hydroelectric dam, in move seen as showing greater openness to public opinion.

2011 October – Some political prisoners are freed as part of a general amnesty. New labor laws allowing unions are passed.

2011 November- Pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi says she will stand for election to parliament, as her party rejoins the political process.

2011 December – Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visits, meets Aung San Suu Kyi and holds talks with President Thein Sein. US offers to improve relations if democratic reforms continue.

President Thein Sein signs law allowing peaceful demonstrations for the first time; NLD re-registers as a political party in advance of by-elections for parliament due to be held early in 2012.

Burmese authorities agree to truce deal with rebels of Shan ethnic group and order military to stop operations against ethnic Kachin rebels.

2012 January – Government signs ceasefire with rebels of Karen ethnic group.

Pre-publication censorship was scrapped in 2012, but state control of media remains strong

2012 April – NLD candidates sweep the board in parliamentary by-elections, with Aung San Suu Kyi elected. The European Union suspends all non-military sanctions against Burma for a year. EU foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton, British Prime Minister David Cameron and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon visit for talks on moving the democracy process forwards.

2012 May – Manmohan Singh pays first official visit by an Indian prime minister since 1987. He signs 12 agreements to strengthen trade and diplomatic ties, specifically providing for border area development and an Indian credit line.

2012 August – President Thein Sein sets up commission to investigate violence between Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims in the west of the country. Dozens have died and thousands of people have been displaced.

Burma abolishes pre-publication censorship, meaning that reporters no longer have to submit their copy to state censors. In a major cabinet reshuffle President Thein Sein replaces hardline Information Minister Kyaw Hsan with moderate Aung Kyi, the military’s negotiator with opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

2012 September – Moe Thee Zun, the leader of student protests in 1988, returns from exile after Burma removed 2,082 people from its blacklist.

President Thein Sein tells the BBC he would accept opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi as president if she is elected.

2012 November – Visiting European Commission chief Jose Manuel Barroso offers Burma more than $100m in development aid.

Around 90 people are killed in a renewed bout of communal violence between Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims.

President Barack Obama visits to offer “the hand of friendship” in return for more reforms. He urges reconciliation with the Rohingya minority.

The transformation in attitude by the government, recognized by the relaxing of restrictions by the US and other countries, then visits by the Secretary of State and the President, have made Myanmar (or Burma, of which more later) the hottest tourist destination on the planet. But Carol and I will not be doing the usual tourist thing, thanks to Dotty (again, more later).

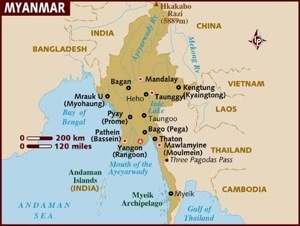

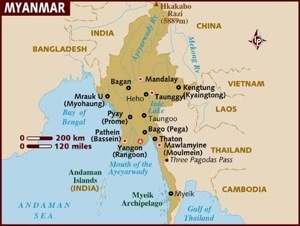

So, first, a bit about Myanmar. Here’s a map to get you situated.

For a very quick summary of the country, I’ve pieced together (stolen) the material below from National Geographic, Wikipedia and the BBC websites. Please excuse the patchwork approach, but I was going for information, not art.

ETHNIC MAKEUP

The majority of Myanmar’s more than forty-eight million people are ethnic Burmans, who are distantly related to the Tibetans and the Chinese. Other ethnic groups (including Shans, Karens, and Kachins) add up to some 30 percent of the population. Ethnic minorities are dominant in border and mountainous areas: Shan in the north and northeast (Indian and Thai borders), Karen in the southeast (Thai border), and Kachin in the far north (Chinese border). The military regime has brutally suppressed ethnic groups wanting rights and autonomy, and many ethnic insurgencies operate against it.

Burman dominance over Karen, Shan, Rakhine, Mon, Rohingya, Chin, Kachin and other minorities has been the source of considerable ethnic tension and has fuelled intermittent protests and separatist rebellions. Military offensives against insurgents have uprooted many thousands of civilians. Ceasefire deals signed in late 2011 and early 2012 with rebels of the Karen and Shan ethnic groups suggested a new determination to end the long-running conflicts.

BRIEF HISTORY SINCE 1800 UNDER BRITAIN

The country was colonized by Britain following three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824–1885). British rule brought social, economic, cultural and administrative changes.

With the fall of Mandalay, all of Burma came under British rule, being annexed on 1 January 1886. Throughout the colonial era, many Indians arrived as soldiers, civil servants, construction workers and traders and, along with the Anglo-Burmese community, dominated commercial and civil life in Burma. Rangoon (Yangon) became the capital of British Burma and an important port between Calcutta and Singapore.

Burmese resentment was strong and was vented in violent riots that paralysed Yangon on occasion all the way until the 1930s. Some of the discontent was caused by a disrespect for Burmese culture and traditions such as the British refusal to remove shoes when they entered pagodas. Buddhist monks became the vanguards of the independence movement. U Wisara, an activist monk, died in prison after a 166-day hunger strike to protest a rule that forbade him from wearing his Buddhist robes while imprisoned.

On 1 April 1937, Burma became a separately administered colony of Great Britain and Ba Maw the first Prime Minister and Premier of Burma. Ba Maw was an outspoken advocate for Burmese self-rule and he opposed the participation of Great Britain, and by extension Burma, in World War II. He resigned from the Legislative Assembly and was arrested for sedition. In 1940, before Japan formally entered the Second World War, Aung San (father of Aung San Suu Kyi) formed the Burma Independence Army in Japan.

A major battleground, Burma was devastated during World War II. By March 1942, within months after they entered the war, Japanese troops had advanced on Rangoon and the British administration had collapsed. A Burmese Executive Administration headed by Ba Maw was established by the Japanese in August 1942. Wingate’s British Chindits were formed into long-range penetration groups trained to operate deep behind Japanese lines. A similar American unit, Merrill’s Marauders, followed the Chindits into the Burmese jungle in 1943. Beginning in late 1944, allied troops launched a series of offensives that led to the end of Japanese rule in July 1945. However, the battles were intense with much of Burma laid waste by the fighting. Overall, the Japanese lost some 150,000 men in Burma. Only 1,700 prisoners were taken.

Although many Burmese fought initially for the Japanese, some Burmese, mostly from the ethnic minorities, also served in the British Burma Army. The Burma National Army and the Arakan National Army fought with the Japanese from 1942 to 1944, but switched allegiance to the Allied side in 1945.

Following World War II, Aung San negotiated the Panglong Agreement with ethnic leaders that guaranteed the independence of Burma as a unified state. In 1947, Aung San became Deputy Chairman of the Executive Council of Burma, a transitional government. But in July 1947, political rivals assassinated Aung San and several cabinet members.

MILITARY RULE

Independence from Britain in 1948 was followed by isolationism and socialism. On 2 March 1962, the military led by General Ne Win took control of Burma through a coup d’état and the government has been under direct or indirect control by the military since then. Between 1962 and 1974, Burma was ruled by a revolutionary council headed by the general, and almost all aspects of society (business, media, production) were nationalized or brought under government control under the Burmese Way to Socialism which combined Soviet-style nationalization and central planning with the governmental implementation of superstitious beliefs. A new constitution of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma was adopted in 1974, until 1988, the country was ruled as a one-party system, with the General and other military officers resigning and ruling through the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP). During this period, Burma became one of the world’s most impoverished countries.

There were sporadic protests against military rule during the Ne Win years and these were almost always violently suppressed. On 7 July 1962, the government broke up demonstrations at Rangoon University, killing 15 students. In 1974, the military violently suppressed anti-government protests at the funeral of U Thant. Student protests in 1975, 1976 and 1977 were quickly suppressed by overwhelming force.

In 1988, unrest over economic mismanagement and political oppression by the government led to widespread pro-democracy demonstrations throughout the country known as the 8888 Uprising. Security forces killed thousands of demonstrators, and General Saw Maung staged a coup d’état and formed the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). In 1989, SLORC declared martial law after widespread protests. The military government finalized plans for People’s Assembly elections on 31 May 1989. SLORC changed the country’s official English name from the “Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma” to the “Union of Myanmar” in 1989.

In May 1990, the government held free elections for the first time in almost 30 years and the National League for Democracy (NLD), the party of Aung San Suu Kyi, won 392 out of a total 489 seats (i.e., 80% of the seats). However, the military junta refused to cede power and continued to rule the nation as SLORC until 1997, and then as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) until its dissolution in March 2011.

On 23 June 1997, Burma was admitted into the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). On 27 March 2006, the military junta, which had moved the national capital from Yangon to a site near Pyinmana in November 2005, officially named the new capital Naypyidaw, meaning “city of the kings”.

In August 2007, an increase in the price of diesel and petrol led to a series of anti-government protests that were dealt with harshly by the government. The protests then became a campaign of civil resistance (also called the Saffron Revolution), led by Buddhist monks, hundreds of whom defied the house arrest of democracy advocate Aung San Suu Kyi to pay their respects at the gate of her house. The government finally cracked down on them on 26 September 2007. The crackdown was harsh, with reports of barricades at the Shwedagon Pagoda and monks killed. However, there were also rumours of disagreement within the Burmese armed forces, but none was confirmed. The military crackdown against unarmed Saffron Revolution protesters was widely condemned as part of the International reaction to the 2007 Burmese anti-government protests and led to an increase in economic sanctions against the Burmese Government.

In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis caused extensive damage in the densely populated, rice-farming delta of the Irrawaddy Division. It was the worst natural disaster in Burmese history with reports of an estimated 200,000 people dead or missing, and damage totaled to 10 billion dollars (USD), and as many as 1 million left homeless. In the critical days following this disaster, Burma’s isolationist government hindered recovery efforts by delaying the entry of United Nations planes delivering medicine, food, and other supplies.

In early August 2009, a conflict known as the Kokang incident broke out in Shan State in northern Burma. For several weeks, junta troops fought against ethnic minorities including the Han Chinese, Va, and Kachin. From 8–12 August, the first days of the conflict, as many as 10,000 Burmese civilians fled to Yunnan province in neighboring China

ECONOMY

Myanmar is a resource-rich country with a strong agricultural base, and is a leading producer of gems, jade, and teak. However, military rule prevented the economy from developing, and the Burmese people remain poor.

A largely rural, densely forested country, Burma is the world’s largest exporter of teak and a principal source of jade, pearls, rubies and sapphires. It has highly fertile soil and important offshore oil and gas deposits. Little of this wealth reaches the mass of the population.

The economy is one of the least developed in the world, and is suffering the effects of decades of stagnation, mismanagement, and isolation. Key industries have long been controlled by the military, and corruption is rife. The military has also been accused of large-scale trafficking in heroin, of which Burma is a major exporter.

The EU, United States and Canada imposed economic sanctions on Burma, and among major economies only China, India and South Korea have invested in the country.

Burma’s wealth of Buddhist temples has boosted the increasingly important tourism industry, which is the most obvious area for any future foreign investment.

Industry: Agricultural processing; knit and woven apparel; wood and wood products; copper, tin, tungsten, iron, gems, jade

Agriculture: Rice, pulses, beans, sesame; hardwood (teak); fish

Exports: Gas, wood products, pulses, beans, fish, rice

When Carol and I originally planned this trip, we did it through a California travel agent. We had a very good and traditional tourist itinerary all set up, but then we met Dotty Guyot, through our friends, Sharon Silverman and David Zimberoff. Dotty was a college classmate of David’s, obtained a PhD in Southeast Asian studies from Yale (thesis: the Japanese occupation of Burma during World War II) and has lived in Myanmar for nine years. She and her husband Jim run an English language, precollegiate school for talented high school graduates in Yangon. Students complete a one-year course and then are placed in universities, primarily in the US and Japan. Carol and I have gotten to know one of their graduates, Arkar Hein, who is now a sophomore at Northwestern University.

Dotty has enthusiastically offered to structure our trip and to introduce us to many people in different walks of life. We have jumped at her offer and abandoned our original plans in favor of Dotty’s recommendations, with the help of a local travel agent, Thiri, who Dotty put us in touch with. You will be reading a great deal about the plans that Dotty has made for us in this blog, as they constitute the backbone of our trip.

So, this is your rather helter-skelter introduction to Myanmar and how our trip came about. We’ll try to fill in some of the gaping holes and add a little order to the chaos as we progress on our journey.

|

|