June 18.

Today we rise very early, 4:30 am and get on our way by 5, since we have a variety of habitats that we want to explore. We are picked up by our birding guide, Josue. The hotel has packed box breakfasts for us.

Our drive to Guango Lodge initially leads us through the drier central valley where we pass through a mix of agricultural zones and native chaparral forests before rising up steeply to the high and (often) windswept paramo.

We are told that this is the day to have a camera ready, because on clear days the scenery is spectacular, with superb views of the snow-capped Volcán Antisana, and seemingly endless high Andean mountain-scapes harboring a backdrop of textures that make for an unforgettable birding setting. Unfortunately, it rained the whole way, so we’ll have to hope to catch the scenery on our way back in two days.

We arrive at the Guango Lodge much earlier than expected, because we did not stop to photograph or bird in the rain. . We arrive at Guango, where the hummingbird feeders are dripping with species of hummingbirds. Because it continues to rain, we do not stay at the lodge until lunch, but continue on to San Isidro. At one point, we are stopped, because the rain has caused a mudslide that blocks the road and needs to be cleared. At San Isidro it continues to rain, but we see more hummingbirds, and a few other species as well. I’m pleased that the inexpensive Canon I’ve bought for this trip is taking some pretty decent bird photos.

We have a good, typical Ecuadorian lunch, which includes tilapia civiche, fried pork nuggets and an interesting egg dish. We then retire to our modest, but adequate cabin for a nap.

At 3:30 it appears to have cleared some, so we don borrowed large, rubber boots and set out in search of birds. We see a few quick glimpses, but nothing much and in half an hour or so it begins to drizzle, so we head back to our cabin.

After resting, we return to the main area, look at some more hummingbirds and then have quite a good buffet dinner. We sit with a couple from the Oakland, CA. who we spend a delightful couple of hours talking with. Alan is the head of the California Audobon society, and Carol is a former professor at UCLA-Berkeley in natural biology. We may well stay in touch with them, as we’ve exchanged contact information.

Today was one of the kinds of days you have to anticipate and accept when you travel. When the weather sucks, it affects your experience. Still, it was far from a disaster; we like our guide very much, the hummingbirds were excellent, my new camera works, talking with Alan and Carol was fun–and I got my luggage back.

June 17.

Okay, here are a couple photos of our hotel that don’t come close to doing it justice. I have no idea what this place costs (because we pay a price for the entire trip, and it’s not broken down), but if you ever have the chance to stay at the Hotel Casa Gagontena–DO!! It’s really quite spectacularly elegant. (Small, dumb example: At the table that has juices for breakfast, there’s also a chilled bottle of champagne. Okay, I know that that may be a bit obnoxious. But I like the idea, even tough we did not partake.) You know that Carol and I have been around a bit, and this hotel fits right up near the top ranks of the truly memorable. Service is terrific, too. Sometimes a hotel is just a place to sleep, and sometimes it becomes an important part of the trip experience.

After breakfast at the hotel, we are met by Diana, and set out on a tour of Quito, a city of some 2.2 million people. We walked around the old city, which is quite charming, with cobblestone ans narrow streets going up hills. In Independence Square we saw some older people protesting a bus fare increase. And there are large signs, welcoming the Pope, who will visit this 80% Catholic country early next month.

We visited the San Francisco Convent and Church, which is right across the street from our hotel. Interesting art work and impressive church, which is (the oldest in Quito and the largest religious complex in South America) and fronted by a large cobblestone square. We also visited the main Cathedral, La Compañía Church (considered one of the continent’s most spectacular monumental buildings), which is heavily guilder with gold. While these stops are interesting enough, frankly, we may already have exceeded our lifetime church quota. By now, I was feeling the altitude a bit, though I drank a lot of water, as advised.

We drove to a market, loaded with fruit, vegetable, meat and people eating, which was more fun than the churches (though we’re not far from reaching our lifetime market limit, too.

Far and away the highlight our day was our visit to the Around midday, we will visit Capilla del Hombre (Chappel of Man), one of the most important museum and art galleries in the country that shows the work of famous artist Oswaldo Guayasamin. Neither Carol nor I had ever heard of this artist, but we’re enormously moved by his monumental paintings depicting anger, grief and hope of people who have been murdered and subjected to mistreatment by governments over the centuries. His work had elements of Goya, Ben Shahn and Picasso, but we’re uniquely his own. He died in 1999, leaving this enormous legacy of which we were totally ignorant. If there’s one thing people visiting Quito should see, based on our experience, it’s Gyayasamin’s work. I can’t begin to represent it here, as I was allowed only one photo from the doorway. The museum is in the fashionable Northeast section of Quito, which affords beautiful views of the city.

Diana drove us through the new portion of Quito, then for a brief stop to see the huge Neogothic Cathedral that was funded by the people, took some ninety years to build and was opened by Pope John Paul in 1985.

Back to the hotel for high tea.

At 6:30, we have arranged to meet Susi and Franklin Hecht at our hotel. The Hechts live in Quito and are long-time clients and friends of our Brandeis classmate, Len Oshinsky, who put us in touch. Oddly enough, Len had written to us some eight months or so ago to tell us that the Hecht’s daughter, Jessica, and her husband, Esteban, had moved to Chicago. At the time, Ecuador was not even on our radar screen as a possible travel destination. We met Jessica, who we loved (Esteban was not available the night we had dinner). And now, we have the chance to meet Susi and Franklin. These sort of charmed and chance coincidences are what make travel, and life, interesting. We had a very nice dinner at an Italian restaurant overlooking Independence a Plaza, and a great chance to hear about them and their children. Franklin is unhappily having to return to the bakery business from which he retired, because of problems in the business. Though he and Susi have rented an apartment for a month in Chicago in September, Franklin is now unsure whether he will be able to come.

After dinner, Susi and Franklin walked us back to the hotel and we said good night. Though they have said they’d like to,get together again, our tight schedule makes that unlikely. Our luggage had not arrived at the hotel, but the latest was that it was expected at 11:30. We told the desk not to bring it up to the room, since we are getting up at 4:30 tomorrow morning.

Note: we’ve had internet difficulties, which prevented posting this yesterday. We’ll do our best, but it could happen again.

June 16, 2015

Well, we’re off to Ecuador. This is a special trip for us, for reasons I’ll disclose in a later post.

But, for now, thoughts about what’s ahead.

Compared to what we’re used to, this should be an easy trip. We fly through Miami to Quito, and the flight to Quito is just over four hours (that is, assuming we make our Miami connection, as we have only an hour and a quarter). Once we get to Quito, the birding lodges we’ll go to are all less that three hours drive. Quito is on the same time as Chicago, which makes a huge difference in ease of adjustment to the flights. And we don’t even need to change money, or worry about conversion rates, because Quito uses the US dollar. Nice of them, eh?

Carol and I have been to, or really through, Ecuador once before. When we went to the Galápagos Islands, probably thirteen years ago or so, we flew through Guayaquil, as that’s where one flied to the Galápagos from. We only spent one night there, as its industrial and not very safe. The trip to the Galápagos was terrific, and became a great influence on our future travel. Having been there, we knew we needed to go to Africa, where we’ve now traveled ten times. Not only were the Galápagos great, but on the same trip we traveled to Peru, including Machu Picchu.

I do have a few doubts about this trip, though. First and foremost is the altitude. Quito is over 9,000 feet (a bit of trivia: Quito is the highest capital city in the world), and the spots we’re going to in the Andes are higher. We have some meds, though, and I’m trusting that they will do the trick.

Second concern is that the only serious birding we’ve done before was in the Pantanal in Brazil last year. We really enjoyed it, and are hoping that this will be equally captivating for us. Related to this is that I got a new camera with a long lens for shooting bird shots and really have not taken sufficient time to learn it. I’ll try to muddle through, though, and the worst case, that I only see, but can’t photograph the birds, would not be tragic. Actually, I suppose that worse than that would be to be unable to find the birds in the new binoculars we’ve bought for the trip. Birds are small, fast and far away, which is not very nice of them.

This will be a short trip for us, 9 days and 8 nights, but because the distance is not too great and we have only a single purpose, birding, that should be manageable. In any case, I’m looking forward to this getaway for just the two of us, after a trip to Namibia with a group of eight, plus a leader and guides.

Glad that you’re along, though, and hope that hearing about how we went out each day and saw birds won’t make for dull reading. I’ll try to spice it up, somehow.

So, we’re en route to Miami, and I encounter three serious problems. First, I work one of those damn Sodukos in the airline magazine. The hard one, only it’s not hard, it’s impossible. I finally crack it, I think, only to find that I’ve made a mistake. And you can’t fix mistakes in Sodukos. I hate these damn, defective Sodukos.

So, then, as the “fasten seat belt sign” is not on, I decide to use the lavatory, since my hands are full of ink from that damn, defective Soduko. And I have another reason, too, which a sense of decorum prevents my disclosing. By the way, did you ever notice how airplanes are the only places that have lavatories, instead of bath rooms or wash rooms? Anyway, I wait outside my lavatory. And the lavatory across the way changes hands (or, maybe, butts) four times, but mine is still occupied. Finally, I knock, which succeeds in convincing some lady that maybe she needs to share her lavatory. Harrumph. I mean, really.

Anyway, I had picked up the Soduko and gone to the lavatory to avoid having to read a book of essays, the first of which I read the other day and did not understand, but which have been assigned as reading for our book group. So, I no longer have an excuse to avoid it, so I tap the Kindle app on my iPad, and the damn thing won’t open. Frankly, I don’t know whether this is good news or bad news. But, harrumph again.

I become so bored–and Carol, who is reading a real book/book won’t talk to me–that I fill out an application for another credit card I don’t need or want, which promises me 50,000 miles that I probably won’t use and waives the $95 annual fee, but renews automatically and I’ll forget to cancel and then have to wait on the phone for 27 minutes and argue with them to cancel the fee. And that’s a fourth serious problem.

So, I have nothing left to do but blog about these travails. Sorta makes you wish for more Ecuadorian history, doesn’t it?

Made our connecting flight to Quito with no difficulty. And so did one of our bags–Carol’s. Spent ages waiting for my bag, then making a claim. They say the bag is in Miami and will arrive at 1PM tomorrow. We’ll see. Shouldn’t take me long to decide what to wear.

After we clear customs, we are met by our very cute guide, Diana, who has lived briefly in California and DC, and is the single mother of 6-month old Sophie, Diana drives us about 45 minutes to our hotel, in the center of Quito. Our travel agent had originally booked us into a large, upscale chain hotel, but I asked whether there wasn’t something with a local flavor, so we are at Casa Gangotena Hotel, which is a former private home, and spectacularly elegant. The fellow at the check-in desk asked us for a copy of our claim check and said they’d follow up tomorrow. Clearly, we are not the first to have lost our bags. Though it’s midnight, he brings out finger sandwiches and has toilet articles and a shirt (!) brought up to the room. I’ve almost forgotten about damn American Airlines. We shower and retire.

Okay, so are you packed, ready to go see some fabulous birds in Ecuador?

First, more than you’d ever want to know about that country.

Ecuador, about equal in area to Nevada, is in the northwest part of South America fronting on the Pacific. To the north is Colombia and to the east and south is Peru. Two high and parallel ranges of the Andes, traversing the country from north to south, are topped by tall volcanic peaks. The highest is Chimborazo at 20,577 ft. The Galápagos Islands (or Colón Archipelago: 3,029 sq mi), in the Pacific Ocean about 600 mi west of the South American mainland, became part of Ecuador in 1832.

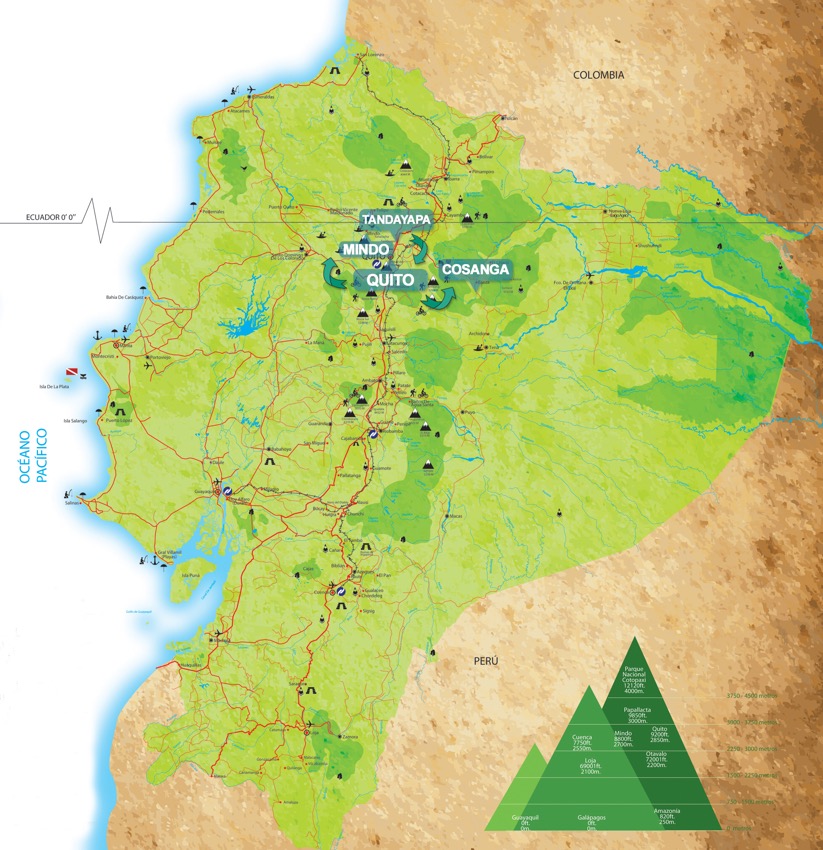

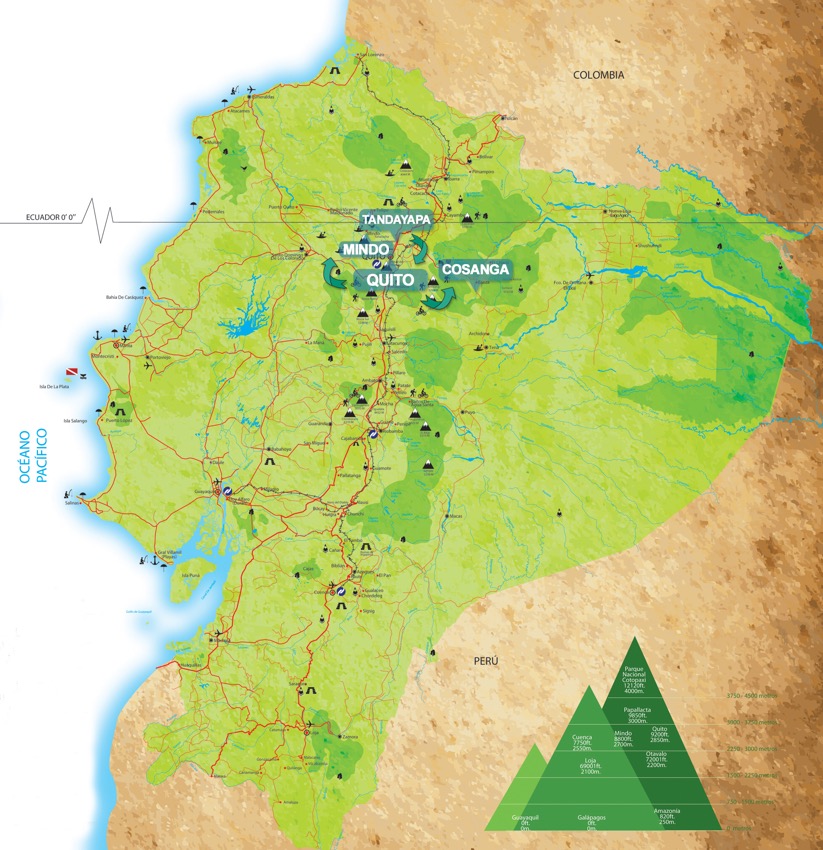

Here’s a map of Ecuador. We’ll be flying into Quito, the capital and the birding we’ll be doing is in the Andes, in the areas marked on the map, north and east of Quito.

Ecuador’s official language is Spanish, but Quichua – an Incan language – is spoken by the Indian population. Besides Spanish, ten native languages are spoken in Ecuador. English is the most spoken foreign language amongs service providers and professionals. The population of Ecuador is 15 million people.

The Afro-Ecuadorians present in Ecuador today are famous for their marimba music and many music and dance festivals. Long before the Spanish conquered Ecuador and even before the rise of Incan civilization, the diverse native cultures of the region had rich musical traditions. Music played an important role in the ancient Andean people’s lives and archaeologists have found drums, flutes, trumpets and other musical artifacts, in ancient tombs.

The Ecuadorians have a distinctive type of dress code. The men and especially the woman in each region of Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands can be easily identified by their dress as it is displays specific cultural diversities that are characteristic of that particular region. A major aspect of Indian identity is present in Ecuador. People that are familiar with the native dress can often tell roughly where an Indian is from, based on what they wear.

So, Ecuadorian culture is not one single culture, but a whole range of cultures mingled together, representing every level of this very stratified community.

Pre-Inca Era History

Before the arrival of the Incas, the area was settled by various peoples. Some likely sailed to Ecuador by rafts from Central America, others came to Ecuador via the Amazon tributaries, others descended from northern South America, and others ascended from the southern part of South America through the Andes or by sailing on rafts. They developed different languages while emerging as unique ethnic groups.

Even though their languages were unrelated, these groups developed similar cultures because they lived in the same environment. The people of the coast developed a fishing, hunting, and gathering culture; the people of the highland Andes developed a sedentary agricultural way of life; and the people of the Amazon basin developed a nomadic hunting and gathering way of life.

Over time these groups began to interact and intermingle with each other so that groups of families in one area became one community or tribe, with a similar language and culture. Many civilizations arose in Ecuador, each developing its own distinctive architecture, pottery, and religious interests.

In the highland Andes mountains, where life was more sedentary, groups of tribes cooperated and formed villages; thus, the first nations based on agricultural resources and the domestication of animals were formed. Eventually, through wars and marriage alliances of their leaders, a group of nations formed confederations.

Inca era

When the Incas arrived, they found that these confederations were so developed that it took them two generations of to absorb the confederations into the Inca Empire. The native confederations that gave them the most problems were deported to far away areas of Peru, Bolivia, and north Argentina. Similarly, a number of loyal Inca subjects from Peru and Bolivia were brought to Ecuador to prevent rebellion. Thus, the region of highland Ecuador became part of the Inca Empire in 1463 sharing the same language.

By contrast, when the Incas made incursions into coastal Ecuador and the eastern Amazon jungles of Ecuador, they found both the environment and natives more hostile. As a result, Inca expansion into those areas was hampered. The natives of the Amazon jungle and coastal Ecuador remained relatively autonomous until the Spanish soldiers and missionaries arrived in force. They were the only groups to resist Inca and Spanish domination, maintaining their language and culture well into the 21st century.

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, the Inca Empire was involved in a civil war. The untimely death of both the heir Ninan Cuchi and the Emperor Huayna Capac, from a European disease that spread into Ecuador, created a power vacuum between two factions, each headed by one son. A number of bloody battles took place until finally Huáscar was captured. Atahualpa marched south to Cuzco and massacred the royal family associated with his brother. Typical family squabble.

A small band of Spaniards headed by Francisco Pizarro landed in Tumbez and marched over the Andes Mountains until they reached Cajamarca, where the new Inca Atahualpa was to hold an interview with them. Valverde, the priest, tried to convince Atahualpa that he should join the Catholic Church and declare himself a vassal of Spain. This infuriated Atahualpa so much that he threw the Bible to the ground. At this point the enraged Spaniards, with orders from Valverde, attacked and massacred unarmed escorts of the Inca and captured Atahualpa. Pizarro promised to release Atahualpa if he made good his promise of filling a room full of gold. But, after a mock trial, the Spaniards executed Atahualpa by strangulation. Nice guys, the Spaniards.

Colonization

New infectious diseases, endemic to the Europeans, caused high fatalities among the indigenous population during the first decades of Spanish rule, as they had no Immunity. This was a time when the natives were also forced into the labor system for the Spanish. In 1563, Quito became the seat of an administrative district of Spain and part of Peru and later of New Granada.

After nearly 300 years of Spanish colonization, Quito was still a small city numbering 10,000 inhabitants. On August 10, 1809, the city’s creole people first called for independence from. Quito’s nickname, Light of America, is based on its leading role in trying to secure an independent and local government. Although the new government lasted no more than two months, it had important repercussions and was an inspiration for the independence movement of the rest of Spanish America.

Independence

On October 9, 1820, Guayaquil became the first city in Ecuador to gain its independence from Spain. The people were very happy about the independence and celebrated, which is now Ecuador’s independence day, officially on May 24, 1822. The rest of Ecuador gained its independence after Antonio José de Sucre defeated the Spanish Royalist forces at the Battle of Pichincha, near Quito. Following the battle, Ecuador joined Simón Bolívar’s Republic of Gran Colombia – joining with modern-day Colombia and Venezuela. In 1830 it separated from those nations and became an independent republic.

The 19th century for Ecuador was marked by instability, with a rapid succession of rulers. The first president of Ecuador was the Venezuelan-born Juan José Flores, who was ultimately deposed, followed by several authoritarian leaders incluiding Flores’s own son, Antonio Flores Jijón. The conservative Gabriel Garcia Moreno unified the country in the 1860s with the support of the Roman Catholic Church. In the late 19th century, world demand for cocoa tied the economy to commodity exports and led to migrations from the highlands to the agricultural frontier on the coast.

Ecuador abolished slavery and freed its black slaves in 1851.

Liberal Revolution

The Liberal Revolution of 1895 under Eloy Alfaro reduced the power of the clergy and the conservative land owners. This liberal wing retained power until the military “Julian Revolution” of 1925. The 1930s and 1940s were marked by instability and emergence of populist politicians, such as five-time President José María Velasco Ibarra.

Loss of claimed territories since 1830

In the 1800s Ecuador had several different disputes with countries over aspects of its territory, leading to conflicts with Gran Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Chile, in addition to the struggle with Spain for independence. I was going to detail these struggles for you, until I decided that they would bore you to tears, so I hope you’re grateful for this abridged version. The land disputes lasted until late in the 20th century, when on October 26, 1988 Ecuador and Peru signed the Brasilia Presidential Act peace agreement, which ended hostilities, and effectively put an end to the Western Hemisphere’s longest running territorial dispute.

Military governments (1972–79)

In 1972, a “revolutionary and nationalist” military junta overthrew the government of Velasco Ibarra. The coup d’état was led by General Guillermo Rodríguez and executed by navy commander Jorge Queirolo G. The new president exiled José María Velasco to Argentina. He remained in power until 1976, when he was removed by another military government. The civil society more and more insistently called for democratic elections. Colonel Richelieu Levoyer, Government Minister, proposed and implemented a Plan to return to the constitutional system through universal elections. This plan enabled the new democratically elected president to assume the duties of the executive office.

Return to democracy

Elections were held on April 29, 1979, under a new constitution. Jaime Roldós Aguilera was elected president, garnering over one million votes, the most in Ecuadorian history. He took office on August 10, as the first constitutionally elected president after nearly a decade of civilian and military dictatorships and governed until May 24, 1981, when he died along with his wife and the minister of defense, Marco Subia Martinez, when his Air Force plane crashed in heavy rain near the Peruvian border. Many people believe that he was assassinated, given the multiple death threats leveled against him because of his reformist agenda, deaths in automobile crashes of two key witnesses before they could testify during the investigation, and the sometimes contradictory accounts of the incident.

There followed a period of some fifteen years when various parties traded power.

The emergence of the indigenous population (approximately 25%) as an active constituency has added to the democratic volatility of the country in recent years. The population has been motivated by government failures to deliver on promises of land reform, lower unemployment and provision of social services, and historical exploitation by the land-holding elite. Their movement, along with the continuing destabilizing efforts by both the elite and leftist movements, has led to a deterioration of the executive office. The populace and the other branches of government give the president very little political capital, as illustrated by the most recent removal of President Lucio Gutiérrez from office by Congress in April 2005. Vice President Alfredo Palacio took his place and remained in office until the presidential election of 2006, in which Rafael Correa gained the presidency.

Economy

Ecuador’s economy is the eighth largest in Latin America and experienced an average growth of 4.6% between 2000 and 2006. From 2007 to 2012 Ecuador’s GDP grew at an annual average of 4.3 percent, above the 3.5% average for Latin America and the Caribbean. Ecuador was able to maintain relatively superior growth during the global economic crisis. Unemployment for 2009 in Ecuador was 8.5% because the economic crisis continued to affect the Latin American economies. From this point unemployment rates started a downward trend: 7.6% in 2010, 6.0% in 2011, and 4.8% in 2012.

The extreme poverty rate has declined significantly between 1999 and 2010. In 2001 it was estimated at 40% of the population, while by 2011 the figure dropped to 17.4% of the total population. This is explained to an extent by emigration and the economic stability achieved after adopting the U.S. dollar as official means of transaction, which it did after a banking crisis in 2000. However, starting in 2008 with the bad economic performance of the nations where most Ecuadorian emigrants work, the reduction of poverty has been realized through social spending mainly in education and health.

Oil accounts for 40% of exports and contributes to maintaining a positive trade balance. Since the late 1960s, the exploitation of oil increased production, and proven reserves are estimated at 6.51 billion barrels as of 2011.

In the agricultural sector, Ecuador is a major exporter of bananas (first place worldwide in production and export), flowers, and the seventh largest producer of cocoa. The shrimp, sugar cane, rice, cotton, corn, palm, and coffee productions are also significant. The country’s vast resources include large amounts of timber across the country, like eucalyptus and mangroves. Pines and cedars are planted in the region of La Sierra and walnuts, rosemary, and balsa wood in the Guayas River Basin. The industry is concentrated mainly in Guayaquil, the largest industrial center, and in Quito, where in recent years the industry has grown considerably. This city is also the largest business center of the country. Industrial production is directed primarily to the domestic market. Despite this, there is limited export of products produced or processed industrially. These include canned foods, liquor, jewelry, furniture, and more. The incomes due to the tourism have been increasing during the last years because of the efforts of the Government of showing the variety of climates and the biodiversity in Ecuador

Between 2006 and 2009, the government increased social spending on social welfare and education from 2.6% to 5.2% of its GDP. Starting in 2007, with an economy surpassed by the economic crisis, Ecuador was subject to a number of economic policy reforms by the government that have helped steer the Ecuadorian economy to a sustained, substantial, and focused financial stability and social policy. Such policies were expansionary fiscal policies, of access to housing finance, stimulus packs, and limiting the amount of money reserves banks could keep abroad. The Ecuadorian Government has made huge investments in education and infrastructure throughout the nation, which have improved the lives of the poor.

On December 12, 2008, president Correa announced that Ecuador would not pay $30.6 million in interest to lenders of a $510-million loan, claiming that they were illegitimate, based on the argument that it was odious debt contracted by corrupt and despotic prior regimes. In addition, it claimed that $3.8 billion in foreign debt negotiated by previous administrations was illegitimate because it was authorized without executive decree. Correa’s administration has succeeded in reducing the high levels of poverty and unemployment in Ecuador.

Okay, so I’m guessing that this is probably more history and economic information than many of you feel a need for. But that’s why skimming was invented. I’ll get into less dense stuff on takeoff, Tuesday, June 16.

May 9-10. Start the long trek home with an 11:25 AM flight from Windhoek to Joburg. Nevada and Bob Newman are on the same flight and we hang out together at the Windhoek airport.

Time for some reflections on the trip. First, it was great to have Carol with me, for most of the trip. In recent years, I’ve done a couple photography trips without her, and it’s just not as much fun. Though I wish she’d been on the extension, I understand that she needed to get back to Judson.

The trip was terrific. Logistically, everything went smoothly, the accommodations were excellent, as was the food and wine, and the guides were outstanding (which makes a huge difference). As I said at the outset, Nevada runs a great trip. She’s adventurous and fun. The group, too, was very good. We laughed a lot together. While one always has some group members who you relate to better than others, none were people you would want to avoid at all costs, or even close to that.

A digression here to illustrate the point. On a trip that Carol and I took to Alaska many years ago, with our friends, Valerie and Michael Lewis, we were part of a small group of about twelve people. One of the fellows, Leroy, was a total bore, and never stopped talking. I started designating certain areas as “Leroy free zones” to Carol and the Lewises. We often had choices of two things to do on the trip and I would wait to see what Leroy chose, and then choose the other option. Carol, who in general is a far kinder and more tolerant person than I, explained that Leroy was just lonely, having lost his wife not long ago. I speculated that his wife had suicided to avoid Leroy.

On the other hand, on the same Alaska trip, we met a couple from New York, Burt and Jannie, who became very close friends of ours and with whom we traveled every year. We had a similar experience with a couple from Maryland, Joe and Madeline, who we met on our biking trip to New Zealand. In both cases, the husband has, unfortunately, died, but we remain close friends with, and see, Jannie and Madeline. I’m not sure we’ll have a similar experience on this trip, but that may well be because we were the only couple on the trip.

Back to the trip. Although logistics and accommodations were excellent, in some ways it was not an easy trip. We drove approximately 2000 miles. While that’s an average of only about 150 miles a day, some days covered far more territory than others, and driving 2000 miles in Namibia bears little resemblance to driving that distance in the US. While the vans were very comfortable and the fact that we had two fewer people than anticipated allowed us to spread out some, the air conditioning was not really adequate when we drove in the heat of the day.

In addition to the driving, it was very hot in the middle of the day and dusty or sandy. Walking in the sand, particularly in the dunes area, was not easy. For me, this was complicated by having some knee and/or foot pain during a significant part of the trip. Those pains waxed and waned, though they were not unbearable, and were definitely worth tolerating to experience the trip. Most days, we were up and off very early in the morning and kept going for a long time. Periodic midday rest periods were most welcome. Finally, though, it’s hard to admit, these trips do not get easier as the years go by. I’m not close to being ready to quit, but this realization is part of what compels me to do as much traveling as I can now, rather than waiting.

There were three major components to the trip–cultural, landscape and game viewing. It’s easy for me to identify which of these three I’d have given up, if I had to–the game viewing. It’s not that this aspect was not good–it was–but Carol and I have been very fortunate to do a good deal of this, and more exciting game viewing, before.

The choice between landscape and culture is much more difficult. I’m not really a landscape guy. I like people and culture. But if I had to pick one aspect of this trip that was most special, I would have to pick the landscape of the dunes. They are so spectacular, and so unlike anything we’ve seen before, that they would have to be my top choice on this trip. I’ve never seen such a magnificent and distinctive landscape. The only thing that comes to mind as a comparison is the Grand Canyon.

That said, though, the people and culture were fabulous, too. That’s why I travel–to see and experience people, and how they live. We had a unique opportunity to experience some unusual and, unfortunately, dying cultures. Indeed, while tourism may threaten and ultimately (though, happily, not yet) taint and change these cultures, without tourism some of them might have died already and certainly others would disappear in the not-too-distant future. So, there’s a kind of symbiotic relationship between these cultures and tourism. I think that, as the trip wore on, I became more conscious of the darker aspects of this symbiotic relationship and so became more uncomfortable “exploiting” these cultures for benign, but voyeuristic, purposes.

Experiencing the villages on this trip was quite different than experiencing the rural villages we’ve visited in Ghana and Nigeria. In one sense, we experienced these villages more fully than we have in Ghana (I’ll use that as a shorthand for Ghana and Nigeria), because we were often in these villages for at least two or three hours and several times visited the same village twice. In Ghana, we typically visited a village for an hour, or even less, though we often went back to the same village in subsequent years. In Namibia, our interactions were with individual villagers, whereas in Ghana it was with Chiefs. In Ghana some of the Chiefs have become real friends. We know one another and greet each other warmly. In Namibia, the relationship is with people in the village. For Nevada it’s real, as she goes back from year to year and brings them photos. The rest of us, though, are highly unlikely ever to see these people again.

There was a more “legitimate” reason for visiting the Ghana villages, because our friends (and, to a much lesser extent, we) were helping with long term issues, such as clean water, education, health and agriculture. This legitimacy made the visits to Ghanaian villages more comfortable and less voyeuristic than the visits on this trip. It’s not that I and others on the trip were not genuinely interested in these people and their cultures, but any contribution we might be making to improving their lives was very indirect and incidental. In other words, buying jewelry or crafts is different from building a well, adding a school room or supporting a medical clinic. That’s not to say that what we did in Namibia was “wrong” or lacked value, it was just very different.

I would be very interested to know what the people in the villages in Namibia and Ghana really think of us, and our visits. My hunch is that they would feel very differently about us. I may never know. In retrospect, I think my interest in making a contribution to the church in Namibia is probably a desire to make our Namibia visit a bit more like our Ghana visits.

As you know, this was a photography trip, so let me reflect a bit on that. I probably took around 3500 photos on the trip. That may seem like a lot, but I expect that I took far fewer photos than anyone else (except Carol, of course). In many, perhaps most or even all cases, I think other group members may have taken two or three times the number of photos that I took.

Photography of the villages and the dunes was great fun. The wildlife photography was much less so. Of the 3500 photos I took (of which perhaps 500 or so are wildlife), I imagine that only a couple of the wildlife photos will interest me enough to spend much time revising them. The landscape and village photos will take the bulk of my time.

Though this was not a workshop intended to teach photography, I learned quite a bit. Most helpful were the sessions I had with Nevada reviewing my photos. But also, just watching her work and working along side her and talking with and watching other group member was also instructive. All of the others are more into the equipment and technical aspects of photography than I am. For almost all of our visits they carried two heavy cameras, with multiple lenses and, sometimes, with heavy tripods (I used a small and rather useless tripod a couple times).

For some of the wildlife photography, I used my Nikon, with a 300 mm zoom lens. But I didn’t really like doing it. The damn thing was heavy, and I was out of practice using it. I was a lot happier and more comfortable with my much lighter Sony NEX 7, with an 18-200 mm zoom lens. I intend to compare the Nikon and Sony photos, but my instinct is to stick with the Sony and just accept that there are photos I won’t be able to get.

Sorry to bore you with all this, but, as you can see, I’m still working through some issues. Bottom line is that I think I’m content to remain a rank amateur. Though I’d like to improve and learn, I’m primarily interested in the creative aspects. Clearly there is an overlap between equipment and technical knowledge and creative possibilities, but carrying a lot of heavy equipment and spending a lot of time on technical matters that don’t really interest me would detract from my enjoyment of photography. So, for now, anyway, I’m prepared to trade a bit of creative possibility for comfort. Besides, I can make up for part (though by no means all) of the creative possibilities in the post-processing work of fine tuning and improving images on the computer.

For all of you who have followed, and especially those who have commented or emailed about the blog, thanks for your interest. I enjoy hearing from you, and that’s part of what motivates me to write the blog.

You’ve worked hard, though, so take a break. Our next trip is not until next month.

|

|