After breakfast with the Sugarmans, we drive along the coast to Mamallapuram (formerly called Mahaballipuram). This is a kind of open-air museum of Tamil art in rock, which is the work of students under the patronage of the Pallava rulers. Strewn along the coast are some outstanding examples of 7th century sculpture – forms of temples (not used as temples, but which became the basis for the architecture of future temples), an enormous bas-relief depicting scenes from the Indian epic the Mahabharata, and an amphitheater of six chariot-shaped temples. Entering the first area, you are greeted by an enormous boulder, which appears to rest precariously on a slope, having apparently rolled down long ago from a higher perch. The landmark of this collection of works is the Shore Temple, located right on The Bay of Bengal, a world heritage monument, and the only surviving one from a complex of probably seven temples, the other’s having been claimed by the sea.

We returned to the hotel, where we had several hours to lunch and relax, before being picked up and taken for a lecture/demonstration on the classical Bharatnatyam dance. Bharat Natyam is one of the oldest dance forms in India and was nurtured in the temples and courts of Southern India. The art was handed down as a living tradition under the “Devadasi” system under which women were dedicated to temples to serve the deity as dancers and musicians. They also tended to serve the priests, as unwilling concubines.

As we entered the parking lot of a complex that contained crafts and examples of the architecture of several areas in the South, there was a bus and many cars, which led us to think that, instead of a private demonstration, we were going to be part of a large group. Not so. We were treated to an hour and a quarter performance by girls from ages 9 to 19, who danced with great skill and enthusiasm. Our enjoyment of the program was enhanced significantly by Devika, a well-known former danseuse and an established expert on this particular dance form, who explained the dances and techniques to us.

Back to the hotel for a quick shower, then an excellent dinner outdoors, enjoying cool breezes and tolerating rather loud music from a party near the restaurant. Only disappointment was that they were out of the appetizer I’d wanted, seared sea scallops with Wasabi-infused swordfish roe. Damn.

Fond reunion with the Sugarmans for breakfast, then headed to the lobby to be picked up by our guide, Jay. We’re staying at Vivanti, part of theTaj Hotel group, like the rest we’ve been at. We have a very nice villa, looking out on The Bay of Bengal, with hammocks hung outside, beyond the patio. Place has a nice, resorty feel to it. (Karen says it reminds her of Hawaii.)

We are driven around Chennai, formerly called Madras and the capital city of the Southern state of Tamil Nadu. In the 17th century, Chennai was the economic and political capital of the East India Company, the British trading company which eventually led to the colonization of India. The history of this area goes back to the fourth millennium BC and the local language, Tamil, is the oldest language in India. Economically, Chennai is one of the fastest growing cities in the country attracting investments from both the automobile (known as the Detroit of India) and the information technology sector. Land is rather inexpensive and water, power and other infrastructure is either in place or being planned.

We visit the heavily carved and colorful 16th century Kapleeswarar temple at the Mylapore temple area. As today is the 63rd anniversary of Indian Independence, the Hindu temple is even more teeming with people off for the holiday than usual. The temple is not only a place for prayer, but also a place for meeting, celebration, shelter, learning, performing, and communication, but not for dating (95% of the marriages are arranged marriages). People come bathed and dressed in fine clothes. Jay stresses that the Hindu religion is very tolerant and respectful of everyone’s beliefs, giving people freedom to pray to whichever god they want in the manner that they choose. We stroll leisurely around the temple, observing the goings-on.

After the temple, we continue to the home of Sabita and Kittu Radhakrishnan. Sabita is a charming woman, our age, a renowned chef who has published three cook books, including one for children. We are joined by her 91-year old mother and her 17-year old granddaughter, Aditi, who is considering going to school in Singapore. Sabi has prepared a delicious lunch for us. After lunch, Sabi gives us a slide presentation on Indian textiles and shows us pieces from her excellent collection. She started and ran a textile boutique, has written pieces on textile history and is now active in promoting Indian textiles through non-profits she’s involved with. In addition, she’s a playwright. After 2 1/2hours, we say goodbye to Sabi and Kittu and drive to a nearby crafts area she recommends, where the Sugarmans buy a number of pieces.

We return to the hotel and rest for awhile, before going up to the lobby with the Sugarmans, taking the bottle of wine Carol and I have brought from the Taj in Mumbai. We’re told they won’t open our bottle, so we order some drinks, then go to the very good seafood restaurant in the hotel, where we sit outside, enjoy a lovely sea breeze and succeed in convincing the restaurant to open and serve our bottle of wine–YESSSS.

After a morning massage (I wasn’t about to let Carol one-up me with hers, yesterday), I meet Carol for breakfast, a new (or at least less achy) man. We’re picked up and set out from Aurangabad to the caves at Ellora.

Now a city of two million, for 25 years, starting in the late 17th century, Aurangabad was established by Aurangzeb as capital of the whole mogul territory he conquered, that stretched from Kabul to Rangoon. Aurangzeb was the mightiest of the mogul emperors, and son of the builder of the Taj Mahal, Shah Jeham. Shah Jeham, which means, ruler of the universe, had intended that his older son succeed him. Aurangzeb begged to differ with Daddy, and fought and killed his older brother, then imprisoned his father in the fort at Agra. Aurangzeb ruled for 49 years, until 1707. He was buried, at his wish, among tombs of holy men in a plain tomb. After him, weak moguls ruled and were divided by the East India Company. The mogul rebellion in 1856 was squashed quickly and brutally by the East India Company. An angry Queen Victoria took over and put it under British rule, where it remained until indpendence in 1947.

En route to Ellora, we drive by a large, old English military garrison in Aurangabard, still used as such by the Indian army, and then past one of the gates of the city (there used to be 52, but most have been destroyed). Twenty or thirty minutes later we pass a 12th century fort, some of the walls of which are still there. The landscape is hilly with some hilltop plateaus.

Arriving at Ellora (about a 45-minute drive), we visit the Buddhist, Jain and Hindu caves. (The thirty caves at Ajanta are all Buddhist.) Dating between 600 and 1100 AD, the caves lie along an ancient trading route and are thought to be the work of priests and pilgrims who used this route. Though the caves at Ajanta were “lost” for a thousand years and covered by dense vegetation, before being discovered in 1819 by John Smith, the Ellora caves remained in view and, hence, we’re subjected to vandalism and the elements Twelve of the 34 caves are Buddhist created between 600-800 AD; seventen are Hindu and date between 600-900 AD; and five of the caves are Jain, carved between 800-1100 AD. domain ip .

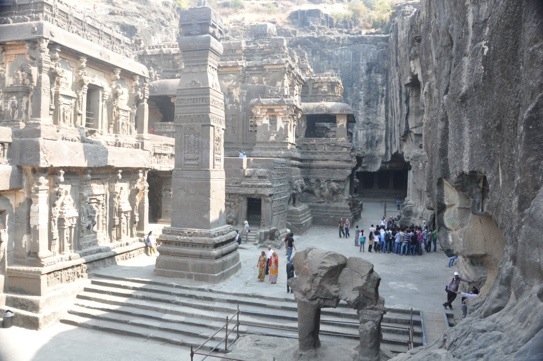

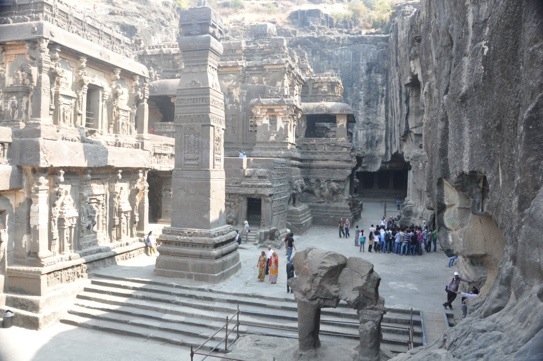

The clear masterpiece of this collection, and the one we visit first, is the magnificent Kailasnatha, a Hindu temple. This is far and away the most outstanding of the rock cut structures at Ellora and is completely open to the elements. It is the only building that was begun from the top. To try to explain what that means, basically, they took a mountain of rock and, carving down from the top, created the entire structure, composed of multiple buildings, sculpture, columns, etc.. You don’t want to make a mistake on a job like that, because whoever is supervising is not going to be pleased. I imagine him saying, “Damnit, Harry, that’s not right. Now let’s just go find another mountain and start over, huh. And, next time time, please watch what you’re doing.”

Begun in 750 AD, Kailasnatha took 150 years to complete. The temple is carved out of 85,000 cubic meters of rock and required that 300,000 tons of rock be removed. Not to get too technical, it’s pretty friggin’ amazing.

After Kailasnatha, everything else is bound to be anticlimactic, and it is. The Buddhist temple, which is carved out of stone from front to back, and top to bottom, as were all of the Ajanta temples and monasteries is excellent, but nothing we haven’t seen at Ajanta. The Jain temple is interesting because of its depiction of Jain figures and because it combines elements of the Hindu and Buddhist, being partially constructed from the top down, creating a building open to the air in front, and the rest carved into the rock in the manner of Buddhist caves.

On the road to and from Ellora, we experience more of the contradictions that are India. The landscape abutting the road is strewn with garbage throughout, migrant settlements dot the fields, yet women walk along the road, or ride on the back of motorcycles, dressed in beautiful, colorful saris. Driving seems suicidal, though we pass a stand built for police to direct traffic with three signs, “Wear Helmets” “Fasten Seat Belts” and “Avoid Sound Pollution”, all of which are uniformly ignored, along with any traffic rules that may exist. The only safe thing on the road is a cow. “Keep Our Containment Clean and Green” reads a banner strung across the road.

Ali has been a very good guide. Very knowledgable about a wide range of subjects, ranging from history to archeology to religion to culture to agriculture and local customs. Interesting fellow, too, planning to go on for a PhD in politics. Lacks the warmth of some guides we’ve had, and speaks very fast, and so sometimes a bit tough to understand, but, overall, quite excellent.

So, is it worth two days out of your vacation to go see a bunch of caves? You betcha.

We’re now en route to Mumbai, where we’ll change planes for Chennai and head to the hotel, where we’ll meet the Sugarmans for breakfast tomorrow.

I must admit that this blogging is fun, if a bit time consuming. It compels you to digest and reflect upon what you are seeing and doing. It’s been gratifying getting some very kind notes from people in different cities and countries saying that they were enjoying the effort.

19.90760275.346118

Nice buffet breakfast at the hotel. Picked up by our guide, Ali, and driver, for a day at Ajanta. We’d come to Aurangabad to see the caves at Ajanta and, tomorrow, the caves at Ellora. As you’ll read, Ajanta is spectacular, but first some reflections on what we see and learn when we travel, borne from the two-hour rides to and from Ajanta.

After fifteen minutes or so of our ride, having had only very limited and brief conversation with Ali, I asked him a question, he answered and I thanked him and said that we’d be interested in hearing anything he’d like to comment on as to what we were passing along the way. This simple invitation unleashed a wealth of commentary, Ali telling us that it would be his privilege and honor to talk about these things, if he would not be getting on our nerves. I said that I’d make him a deal, we’d tell him if he was getting on our nerves and, otherwise, he should assume that we were interested in what he was talking about. It’s clear that, had we not invited his comments, most of the four hours there and back would have passed in silence.

This invitation also opened up a connection between us, as Ali, learning that we were from Chicago, told us that he’d spent two years there, and knew and loved the city well. We began talking about things in the city and he mentioned Brookfield Zoo. We asked whether he’d been there and he said, yes, that he’d seen Bengal tigers there. We said that we’d seen Bengal tigers in Khana National park in central India on our first trip, and we all laughed at the irony of him coming to see Bengal tigers in Chicago and us going to his country to seek them out.

It’s a good question as to what travelers learn about any place they go to. In India, we saw some highlights of Mumbai, we’ll see the caves, we’ve visited fascinating places on our previous trip, such as Varanasi, Delhi, Agra and Udaipur, seen a camel fair in Pushkar and attended an Indian wedding. But, despite the fact that Mumbai and Delhi, together, hold more than 40 million people, Ali told us that 70% of the Indian population is in villages. So, in a sense, we won’t see the real India, and that’s true, too, of the way most of us travel in most countries. (As an aside, Carol and I have been privileged to visit and meet and talk with people in rural villages in both trips we’ve made to Ghana with our good friends, Dick and Susie Kiphart. That’s been fabulous, but, even then, we’re only able to spend very limited time there.)

But, despite our limitations, let me try to give you a brief description of what we learned from/saw with Ali today. Towns teeming with activity because of market day, held on rotating days in villages to give the many people who live in villages far from cities and roads the opportunity to sell and buy goods. Numerous small groups of teepee and tent-like structures, often roofed with tarps, lived in by migrant workers, who leave their villages for eight months a year (returning for the four monsoon months) to work the farms of wealthier people. Many of their children are delivered by midwives in these temporary quarters. Sugar cane and cotton are the main crops. Cotton piled in fields near gin mills. Tiny temples by the roadside for farmers to worship their gods during breaks in their day. Dry river beds of “seasonal” rivers filled in monsoon season. Roadside crematoriums outside towns. Teak, castor, arcadia and banyan trees, which drop roots and grow new trees (“walking” trees). Ghandi white hats worn by farmers (and yesterday’s dabbawallas), a style chosen by Ghandi and continued by Nehru because the hats are simple, cheap, and not Brittish. Cricket match played on a field strewn with litter and encircled by motor bikes of “fans.” Driving on these 2-lane roads is a perpetual game of chicken, encountering other cars, buses, people riding two (or more) to a motor bike, no helmets, women on the back wearing colorful saris, ox-drawn carts, trucks piled high with grains, cotton and people.

All this and more, before even getting to the caves, located two hours from Aurangabad, a modest-sized Indian city of some two million. The caves at Ajanta date from 200 BC to 650 AD and are cut from the volcanic lavas of the Deccan Trap in a steep crescent shaped hillside in a forested ravine. Carol and I elected to forego the easier way to enter the site, instead hiking down from a ridge opposite the site. We’ll undoubtedly pay the price with aches tomorrow, but think it was a good decision.

At the height of its importance, the Ajanta Caves housed over 200 Buddhist monks some of them artists as well as numerous craftsmen and laborers. These caves or vihararas are remarkable for the quality of their carvings and their murals which relate the life story of The Buddha and reveal images of the royal court, ordinary family life, and street scenes. Some of the cave murals relate to the Buddha’s previous births.

It’s impossible to convey just how astounding these monasteries and caves, carved out of a mountain of basalt stone are. The whole complex is essentially a single block of stone. The site is owned by the Indian government and as a World Heritage Site is governed by rules of UNESCO. what is a domain Rather than babble on with more words, I’ll just attach a bunch of photos to try to give some idea of what I’m talking about.

Sorry, but that’s about the best I can do right now.

After arriving back at the hotel late in the afternoon, Carol had a massage and I swam briefly and sat by the pool. We had a lavish Indian barbecue buffet dinner outdoors at the hotel, and were treated to a quite delightful local dance performance by three engaging and brightly-costumed dancers.

If I ever finish this blog, I’m going to collapse and join Carol, who had the good sense to crash a while ago.

19.90759575.346002

Breakfast in the hotel, joined by Sue and her accountant-husband, Herb, who was feeling much better. They got up earlier than they needed to in order to have breakfast with us.

Picked up at 9AM by Joshua and our driver, Mohammed. First stop was the Victoria Terminus, a most impressive building from the outside, but rather disappointing inside. Hustle and bustle was not especially “bustlely” and there was no central hall to compare to any of many we’ve seen in the US. Still, the fact that about a million of Bombay’s five or so million daily railroad commuters pass through it is noteworthy.

Joshua is quite involved in, and very knowledgable about, the Jewish community in India, which now is primarily in Bombay, where some 4000 live. He told us of the two communities in Bombay, an ancient one, of which he is a descendant, called Bene Israel which fled Israel when Antiochus came, and a Baghdadi community, which came from Persia much later. The Sassoon family was part of the latter group and acquired great wealth, first through the opium trade with China (for tea sold to the British), and later through textiles and then banking. Most of the Baghdadi community has now emigrated to England, the US or Israel. Hostility between the two Jewish communities no longer exists.

The Sassoons were responsible for building two of the three synagogues we visited this morning, the Magen David and Knesset Elyahu. The other, Tipheteth Israel is a Bene Israel synagogue.

All three were quite attractive, two of them having balconies for women congregants. Joshua also spoke of the beautiful, but virtually defunct, synagogue we will see in Cochin, and of others, as well. He knew of the Bene Ephraim group that I spoke to Shonali about our visiting in the South, before I concluded that it would be too difficult to do for this trip. His friend, Sharon, who we met outside one of the synagogues, works for ORT in Mumbai and has visited and helped the very poor Bene Ephraim community. Unfortunately, we were unable to reach Sharon later to try to talk to him about Bene Ephraim.

From the synagogues, we drove to see the Dhobi Ghat, an enormous cooperative open air laundry, similar to the one we saw yesterday, but much larger. Laundry is collected by laundrymen, dhobiwallas, and brought to the ghat where different types of laundry is washed by different people and somehow sorted out through small markings and, rather miraculously, returned from whence it came.

An even more amazing version of this type of business are the Dabbawallas, who we saw outside the Church Gate railway station. Every morning the Dabbawallas call on homes in the suburbs to pick up “Dabbas” or lunch boxes of home cooked food prepared for office goers who left at the crack of dawn to take commuter trains into the city. Transporting these lunches on local trains, they gather at Church Gate station to segregate them area wise before they are delivered. Each lunch box looks exactly alike, but without any modern technological equipment, more than 50,000 lunches are delivered on time daily to the correct recipient. It is a system based on memorized codes and leg muscles as they load multiple boxes on to coffin size trays and rush them through the chaos of Mumbai to the correct offices, usually on bicycles.

The Dabbawallas have been studied by The Harvard Business School as an example of teamwork. It is truly amazing to see. As we were watching them, who should pull up in another car but Sue and Herb, our breakfast companions, and their guide Hanna–who happens to be Joshua’s wife! We think Joshua is terrific, have exchanged contact information and hope to stay in touch.

We visited a couple of other modern art galleries with little success, so we abandoned the effort and instead headed for the vegetable, textile, pet and gold markets, walking around to observe and photograph. We returned to the hotel to pack up, blog, email and have a short high tea, before being picked up to head for the airport for our 6:45 flight to Aurangabad.

Driving here is harrowing, a constant beeping of horns, with four lanes regularly converted into six as cars, tuk-tuks and motor cycles stratal the lane markers, which appear to be mere suggestions. We marvel that we don’t see the roadways strewn with the bodies of the unhelmeted motorcyclists who weave in and out at high speeds.

Mumbai is quite an appealing city, and I’d happily return, as we have just scratched the surface. It’s location on the water gives it an open feel that Delhi lacks.

Flight to Aurangabad is short (less than an hour) and uneventful. Our hotel, the Taj Residence, is quite nice, but pales, as almost every hotel in the world would, as compared to the Taj Palace in Mumbai. Security is serious. After checking in, we have a really excellent meal outdoors at the hotel, then return to the room to retire.

19.90757375.346067

|

|